ROCHESTER, Minn. — Scientific breakthroughs in one disease don’t always shed light on treating other diseases. But that’s been the surprising journey of one Mayo Clinic research team. After identifying a sugar molecule that cancer cells use on their surfaces to hide from the immune system, the researchers have found the same molecule may eventually help in the treatment of type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic autoimmune condition in which the immune system errantly attacks pancreatic beta cells that produce insulin. The disease is caused by genetic and other factors and affects an estimated 1.3 million people in the U.S.

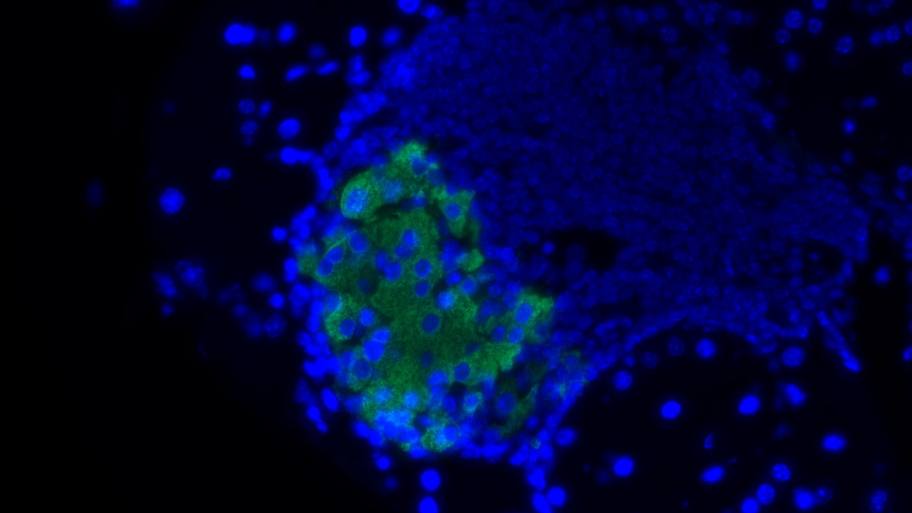

In their studies, the Mayo Clinic researchers took a cancer mechanism and turned it on its head. Cancer cells use a variety of methods to evade immune response, including coating themselves in a sugar molecule known as sialic acid. The researchers found in a preclinical model of type 1 diabetes that it’s possible to dress up beta cells with the same sugar molecule, enabling the immune system to tolerate the cells.

“Our findings show that it’s possible to engineer beta cells that do not prompt an immune response,” says immunology researcher Virginia Shapiro, Ph.D., principal investigator of the study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

A few years ago, Dr. Shapiro’s team demonstrated that an enzyme, known as ST8Sia6, that increases sialic acid on the surface of tumor cells helps tumor cells appear as though they are not foreign entities to be targeted by the immune system.

“The expression of this enzyme basically ‘sugar coats’ cancer cells and can help protect an abnormal cell from a normal immune response. We wondered if the same enzyme might also protect a normal cell from an abnormal immune response,” Dr. Shapiro says. The team first established proof of concept in an artificially-induced model of diabetes.

In the current study, the team looked at preclinical models that are known for the spontaneous development of autoimmune (type 1) diabetes, most closely approximating the process that occurs in patients. Researchers engineered beta cells in the models to produce the ST8Sia6 enzyme.

In the preclinical models, the team found that the engineered cells were 90% effective in preventing the development of type 1 diabetes. The beta cells that are typically destroyed by the immune system in type 1 diabetes were preserved.

Importantly, the researchers also found the immune response to the engineered cells appears to be highly specific, says M.D.-Ph.D. student Justin Choe, first author of the publication. Choe conducted the study in the Ph.D. component of his dual degree at Mayo Clinic Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine.

“Though the beta cells were spared, the immune system remained intact,” Choe says. The researchers were able to see active B- and T-cells and evidence of an autoimmune response against another disease process. “We found that the enzyme specifically generated tolerance against autoimmune rejection of the beta cell, providing local and quite specific protection against type 1 diabetes.”

No cure currently exists for type 1 diabetes, and treatment involves using synthetic insulin to regulate blood sugar, or, for some people, undergoing a transplant of pancreatic islet cells, which include the much-needed beta cells. Because transplantation involves immunosuppression of the entire immune system, Dr. Shapiro aims to explore using the engineered beta cells in transplantable islet cells with the goal of ultimately improving therapy for patients.

“A goal would be to provide transplantable cells without the need for immunosuppression,” says Dr. Shapiro. “Though we’re still in the early stages, this study may be one step toward improving care.”

The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Please see the study for the full list of authors.

###

About Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization committed to innovation in clinical practice, education and research, and providing compassion, expertise and answers to everyone who needs healing. Visit the Mayo Clinic News Network for additional Mayo Clinic news.

Media contact:

- Kelley Luckstein, Mayo Clinic Communications, [email protected]

The post Mayo Clinic researchers find “sugar coating” cells can protect those typically destroyed in type 1 diabetes appeared first on Mayo Clinic News Network.